A comprehensive analysis of on-pack marketing of foods sold in Australian supermarkets has revealed widespread, unregulated use of promotional techniques directly appealing to children—like cartoon characters—most commonly on unhealthy and ultra-processed foods associated with overweight and obesity. This practice is banned in countries where stricter food marketing rules have positively impacted children’s diets.

Conducted by researchers at The George Institute for Global Health and published today in Public Health Nutrition, the analysis of child-directed food marketing highlights a potentially harmful regulatory gap in Australia compared to some lower income countries.

Program Head of Food Policy at The George Institute for Global Health, Professor Simone Pettigrew, said that almost all (96%) products surveyed would carry at least one warning symbol in Mexico (which has the strictest rules) and could not be promoted to children at all, either on packaging or elsewhere including on television or in print advertising, in that country.

“The results confirm concerningly high use of child-directed promotional techniques to market what are essentially the unhealthiest products to Australian families,” Prof. Pettigrew said.

“Parents and caregivers may be surprised to learn that Australia’s regulatory system does not currently provide strong safeguards to protect the future health of our children from harmful food marketing, in contrast with other countries with enforceable rules about on-pack marketing,” she added.

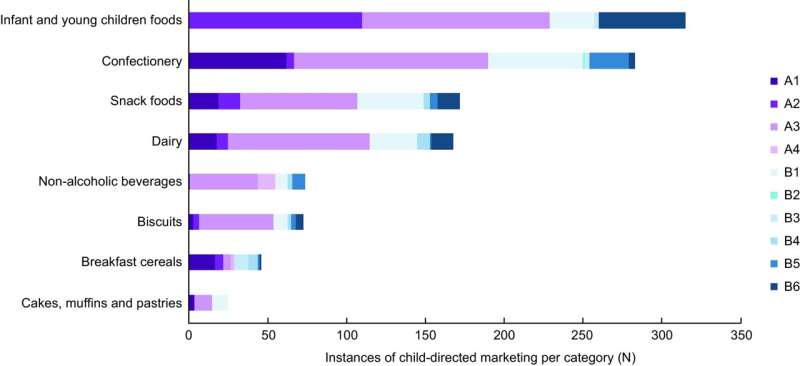

George Institute researchers analyzed 8,006 products across eight categories (those with a higher proportion of child-directed promotion on packs) using the Institute’s FoodSwitch database that collates the nutritional information on the majority of packaged foods sold in Australian supermarkets. These categories were: biscuits, cakes, muffins and pastries; confectionery; breakfast cereals; non-alcoholic beverages; dairy; snack foods; and foods for children aged 0–36 months.

Products were coded by their use of 10 child-directed techniques including use of cartoon and other characters, gifts and contests, and unconventional packaging. Products were also scored on their relative healthiness using four accepted measures—the Australian Health Star Rating system, the NOVA classification system for degree of processing, the WHO nutrient profiling model for the Western Pacific Region (WHO WPRO) and the Mexican nutrient profiling model.

Key findings:

- 1,156 instances of child-directed on-pack promotion were found (11.3% of products analyzed)

- The majority (81%) of these were classified as ultra-processed foods

- Only 6.1% of products would be eligible to be marketed to children under the WHO WPRO model and only 4.5% if Mexican criteria were applied (i.e., 95.5% would have to remove current child-directed marketing elements)

- Child-directed techniques were most common on infant and young child foods (315 instances), followed by confectionery (283), snack foods (172) and dairy products (168)

- 15 major manufacturers produced two thirds of surveyed products that featured child-directed promotions on pack

Prof. Pettigrew said the study is the largest contemporary review in Australia showing a direct correlation between the low nutritional value of packaged foods and high relative use of child-directed promotion, and the first to assess the nation’s food packaging against the most advanced food marketing rules internationally.

“We’re well behind those countries that are prioritizing children’s health over the commercial interests of the food industry,” she added. “Australia’s food marketing regulations are still voluntary and don’t include any restrictions on the use of characters and celebrities, graphics, giveaways and competitions on packaging that appeal to children.

“We’re effectively allowing the food industry to combine ‘pester power’ through children’s emotional connection with characters, with their biological preference for sweet and salty foods—with no legislative protections, this is a public health disaster in the making,” she said.

The introduction of clear, strict laws restricting marketing of unhealthy foods to young people in Chile, Peru and Mexico are changing children’s food habits. In Chile, the use of child-directed promotions on breakfast cereals decreased from 43% to 15% and there has also been a reduction in purchases of foods with a “high in” warning label since the regulations were introduced.

In Australia, restrictions on food marketing have been set by the food and advertising industries through self-regulated codes that contain no provision for child-directed techniques on packaging.

Dr. Sophie Scamps, Independent MP for Mackellar and a former GP, introduced her Healthy Kids Advertising Bill 2023 to Parliament in June in a bid to protect children from junk food marketing.

“The George Institute’s latest research is further evidence that food companies are deliberately targeting children in their marketing of unhealthy foods,” said Dr. Scamps. “Given 25% of Aussie kids are above the healthy weight range, it’s clear that industry self-regulation is not working.

“That’s why I put forward my Healthy Kids Advertising Bill. It’s time government stepped in to restrict food companies from saturating our children with their marketing,” she continued. “We need to create an environment for our children to thrive in, not one where they are preyed upon for profit and paying for it with their health.”

Prof Pettigrew said there is substantial evidence Australia’s food marketing regulations are not protecting children and that stronger rules are needed that enforce penalties for non-compliance.

“The government is strengthening laws to protect children from other known harms including vaping and gambling; given the rise of obesity and overweight in Australian children, and their links to serious health conditions including diabetes, heart disease and some cancers, we urge policymakers to also close this dangerous loophole to protect their future health.”

The George Institute is also calling on the Australian Government to:

- Introduce regulations to limit the use of child-directed promotional techniques on the packaging of unhealthy foods

- Introduce regulations to restrict unhealthy food marketing to children, including ensuring television, radio and cinema are free from unhealthy food marketing from 6:00am to 9:30pm

- Introduce regulations restricting online marketing of unhealthy foods to kids, including on social media

More information:

Alexandra Jones et al, Chocolate unicorns and smiling teddy biscuits: analysis of the use of child-directed marketing on the packages of Australian foods, Public Health Nutrition (2023). DOI: 10.1017/S136898002300215X

Citation:

Aussie kids exposed to aggressive food marketing that would be banned in other countries, finds analysis (2023, November 14)

retrieved 19 November 2023

from https://medicalxpress.com/news/2023-11-aussie-kids-exposed-aggressive-food.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.